How do we respond to the brutal reality of warfare? What narratives can be placed around violent conflict to help us to make sense of something so incomprehensible? And for those who have survived such atrocities, how can individuals and communities support people who have endured attacks in their home country?

If these questions feel increasingly urgent today, they have been similarly confronted throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in the context of international conflict. As the starting point for this belligerent history, the First World War is recognised as a terrible rupture that resulted in the deaths of over eight million allied and enemy forces, as well as unprecedented non-combatant casualties on both sides.

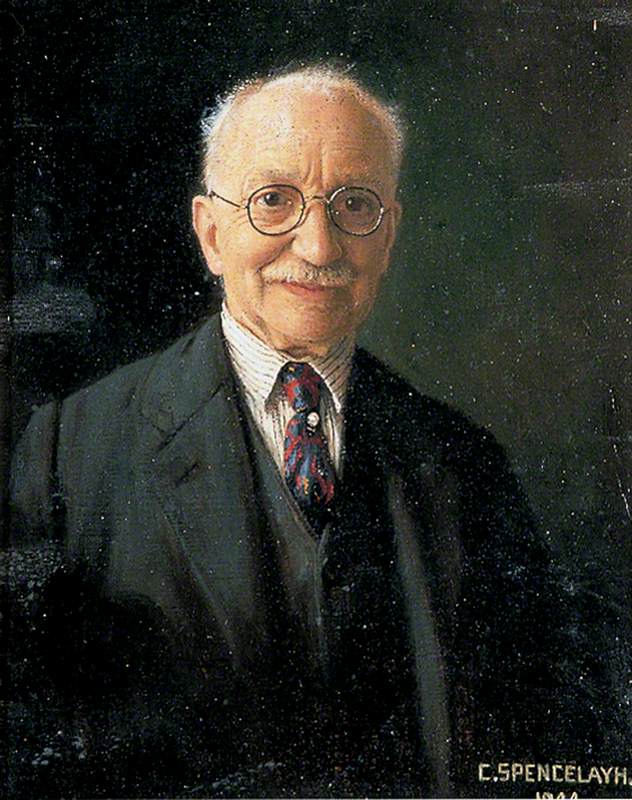

Remember Belgium

c.1914, poster by unknown artist and David Allen and Sons Ltd

In Britain, during the first weeks of the war in the summer of 1914, any signs of the trauma ahead were covered over by jingoistic propaganda, which pitched international hostility as little more than a competitive game.

Yet one episode broke this wargame illusion: the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914. The 'campaign of terror' metred upon its civilian population could not be contained within the government's rhetoric of military bombast. News of atrocities such as the burning of Louvain, in which over 1,000 homes were destroyed and 248 people were brutally executed, filtered across the channel, bringing stories of injury, death and ruination.

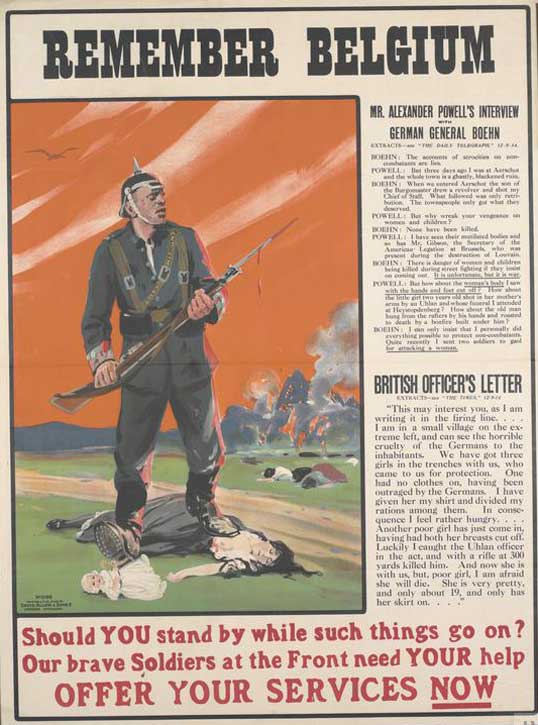

Remember Belgium: Enlist to-day

1914, chromolithograph on paper by Parliamentary Recruiting Committee and Henry Jenkinson Ltd

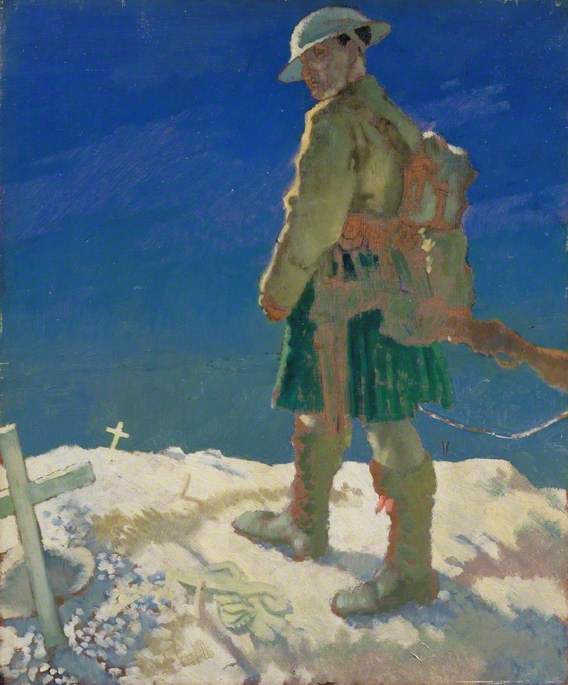

From the beginning, visual culture played a crucial role in how these events were understood in Britain. As the first major wartime incident, the Belgian invasion became the subject of an emotive campaign by the government's Ministry of Information, which portrayed Britain as a dominant imperial power and defender of weaker allied nations. In recruitment posters the identity of the British officer in Belgium was constructed as a 'man of honour' and natural adversary to the 'German Hun' who was, in turn, presented as a ferocious plunderer of defenceless female populations.

This implicit gendering of wartime events also emerged in artists' responses to the invasion. While abuses against women and children became emblematic of Belgium's plight in government propaganda, many artists chose to home in on those fleeing German aggression.

Britannia with Belgian Refugees, created by the Belgian painter André Cluysenaar after he had resettled in Britain in 1915, portrayed the situation through an unambiguously imperialist lens. A helmeted female warrior, Britannia, appears to give shelter to an exhausted mother and baby.

Meanwhile, in Flight, the British artist Thomas Mostyn depicted this movement of people in terms of a Biblical exodus, the procession of anguished women offering insight into the ordeal they had experienced.

Flight (The Belgian Refugees)

c.1914

Thomas Edwin Mostyn (1864–1930)

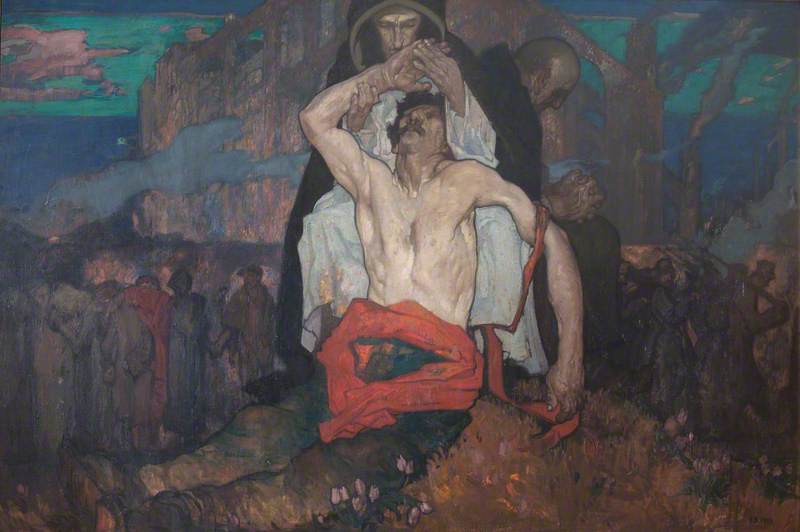

Frank Brangwyn also gave a religious frame to the collective trauma of the Belgian people. In Mater Dolorosa Belgica, the twin concepts of female violation and maternal loss are raised to the level of Christian symbolism by the appearance of the Virgin Mary holding the dead body of Christ. Located in Bruges, Brangwyn's Madonna is set against the city's burning cathedral and flanked on either side by emaciated refugees and advancing soldiers.

Yet, amidst this devastation, the artist offers hope through the resurrection of Jesus and the Christian faith. For Brangwyn this meant extending charity to those affected by the invasion. Having spent his early childhood in Bruges, he was deeply empathetic toward Belgium's struggle. As a result, much of his wartime work, including evocative propaganda posters, was dedicated to raising awareness and funds for the country's beleaguered population.

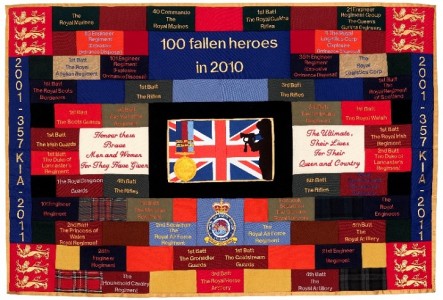

Brangwyn's art fed into a larger campaign of support in the UK. In September 1914, the government offered 'victims of war the hospitality of the British nation', accepting responsibility for the reception and welfare of Belgian refugees. Councils assisted those fleeing military aggression by ensuring that they had access to housing, food, medical care and employment.

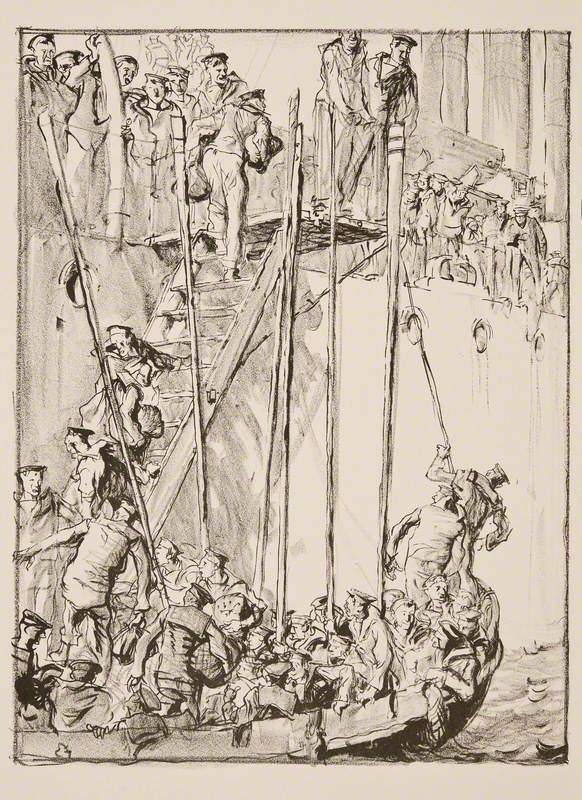

In Landing of the Belgian Refugees, Fredo Franzoni paid tribute to services provided by coastal towns such as Folkestone, which was the entry point for 64,000 of the 250,000 refugees who eventually resettled in Britain.

Alongside assistance from medical and social welfare institutions, the British art establishment played a prominent role in the state's co-ordinated aid effort. From October 1914 it was responsible for organising charity lectures, concerts and exhibitions dedicated to all aspects of Belgian culture from classical music, painting and sculpture to lacemaking and puppetry.

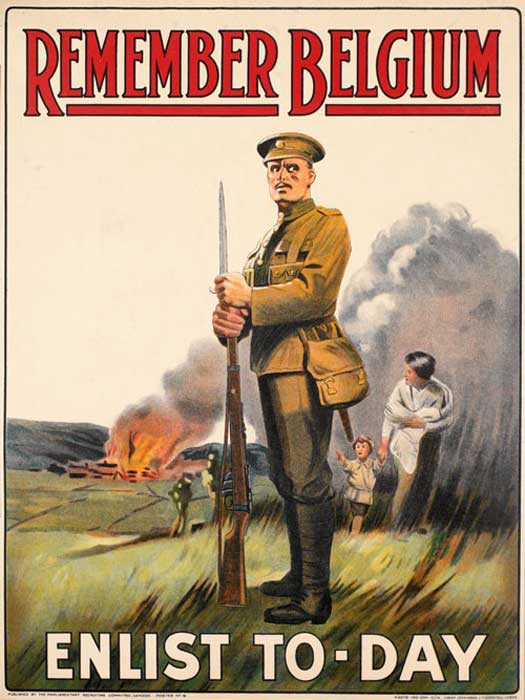

War Relief Exhibition, Belgian Section, in aid of Belgian artists

It is important to recognise that the purpose of these events was not limited to fundraising. Rather, by giving a platform to Belgium's artistic heritage at a moment when its traditions were threatened by German conquest, cultural organisations in the UK underlined the necessity of Britain's military mission to protect European civilisation. As such we might see Belgian relief exhibitions, like that mounted at the Royal Academy in 1915, as propaganda exercises. They were intended to ensure not only the public's continued support for refugees, but also widespread acceptance of the nation's wider war policy.

Several prominent British artists took their lead from this propagandist message. Nevertheless, amongst peace advocates and members of the avant-garde, there was some sense that art should avoid narratives that played into the national directive for a protracted, offensive war.

Unshatterable (Belgian Refugees)

1916, oil on canvas by Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947)

Take for example Frances Hodgkins' Unshatterable (Belgian Refugees), or the painting below by Norah Gray, in which the protagonists are set against empty backdrops and thus divorced from tropes typically associated with the Belgian invasion. Depicting internalised psychological trauma, such images are no less powerful than those by Brangwyn or Cluysenaar. However instead of making a division between German perpetrators and British saviours, Hodgkins and Grey narrowed down the effects of war at an individual, non-partisan level.

Another approach taken by avant-garde artists was to shift the focus away from Belgian refugees as victims. As we have seen, the British state presented Belgian art as traditional and conformist while its citizens featured as little more than passive martyrs. By contrast, modern artists and their patrons welcomed Belgian émigrés as vital contributors to Britain's growing internationalist scene.

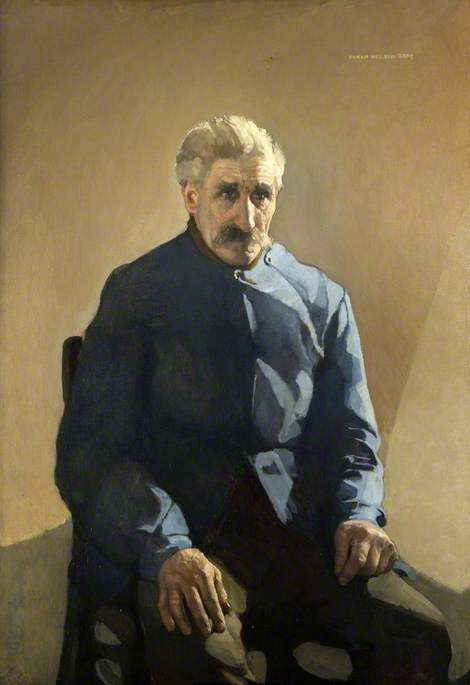

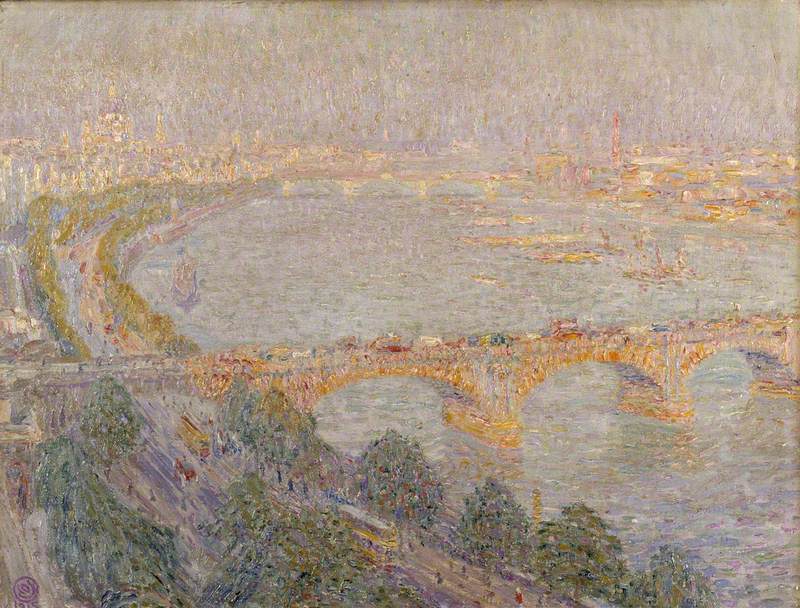

Amongst those to find a home within London bohemia were the Post-Impressionists Edgard Tytgat and Léon de Smet, supported respectively by the painter Ethel Walker and writer John Galsworthy, as well as the composer Marie Weber-Delacre who performed at Roger Fry's Omega Art Circles.

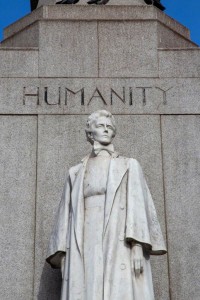

In Wales, the arrival of Symbolist artists such as the painter Valerius de Saedeleer and sculptor George Minne offered exciting potential for cultural renewal, a development that was encouraged by their sponsors, Gwendoline and Margaret Davies.

Today we know that approximately 1,600 Belgian artists sought sanctuary in Britain during the war. What effect did the invasion of their homeland and subsequent displacement have upon them, and how possible was it to continue working in a foreign country? Given the rich body of art created by Belgian refugees, it is clear they faced their situation with determination and resilience.

Nevertheless, their experience of settlement seems less even, an unsurprising outcome if we consider the diverse circumstances they encountered. In the case of Tytgat and de Smet, who were plugged into London's commercial networks, their vibrant, expressionist depictions of popular landmarks and entertainments convey some impression of life continuing, albeit rather artificially. De Saedeleer's compositions are, by contrast, more reflective. For him, the emptiness of the Welsh landscape seemed to provide an effective vehicle for the profound loss he had endured.

Unable to resume his sculptural work in Wales, George Minne underwent perhaps the greatest upheaval. Nevertheless, he overcame this difficulty by making powerful charcoal drawings examining the mother and child motif.

In these pictures we are reminded of the immense suffering borne by the Belgian people, yet here again, the universality of the artist's imagery avoids questions of national responsibility or blame. Instead, his monumental maternal figures exude strength and fortitude, while the babies signify new life. Given these symbolic choices, we might conclude that, rather than merely enduring violent conflict as a kind of rupture, Minne viewed his exile as a period of transformation and regrowth. His work, like that of many Belgian artists who found refuge in Britain, conveys emerging hope and possibility amidst the catastrophe of war.

Katy Norris, art historian and curator specialising in women's politics and modern British art

Further references

Larry Zuckerman, The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War, New York University Press, 2004

Jeff Lipke, Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914, Leuven University Press, 2007

Katherine Storr, Excluded from the Record Women, Refugees, and Relief, 1914–1929, Peter Lang, 2009

Iga Rossi-Schrimpf and Laura Kollwelter (eds), 14/18—Rupture or Continuity, Leuven University Press, 2018

Peter Wakelin, Refuge and Renewal: Migration and British Art, Sansom, 2019

.jpg)